Image Credit: John S. and James L. Knight Foundation (cc-by-sa)

The World Wide Web is at the center of the Internet. Most information you access through your browser (Firefox, Chrome, Safari, Internet Explorer) is formatted and displayed using the techniques originated by Tim Berners-Lee in the early 1990s at the European center for nuclear research, known as CERN.

Image Credit: John S. and James L. Knight Foundation (cc-by-sa)

Berners-Lee was trying to make it easier for scientists to share their work. The network protocols available in the early 1990s didn't have support for a rich mix of text, images, sound, files of data, etc. Very quickly, his first web site and the http protocol he started, grew to many servers. With an expanding protocol structure, researchers quickly saw the value of a common platform for interactive work. The World Wide Web is a collaborative space and is continuing to develop new capabilities. The effort is overseen by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) where Sir Tim now works.

One core feature of the World Wide Web is the link. Any user of a browser these days follows link after link, tracking things that interest them from source to source. It is very easy to start with one idea in your mind and wind up exploring lots of seemingly unrelated stuff by the end of the chain of links you have clicked. Links did not spring instantly into Sir Tim's mind. The terms "hypertext" and "hypermedia" are from Ted Nelson who described his concepts about nonlinear writing with the term back in the mid 1960s. It was the merging of networking technologies with the World Wide Web which made the idea explode into our collective consciousness. Today, we read the news, watch videos, even purchase goods by way of links. The official protocol is known as "hypertext transfer protocol" abbreviated http:// and every browser today adds that to an address when you type it in, even if you don't do it yourself.

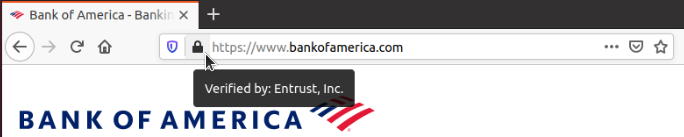

That means www.runeman.org automatically becomes http://www.runeman.org. The destination server knows that you want a hypertext or "web" page delivered to your browser. There are other protocols, but most web users rely on the hypertext protocol for data transfer between your browser and the linked web site.

If you hover your mouse pointer over the small padlock icon at the left end of the address, you'll also see the company which provides the security assurance, in this case, the company Entrust, Inc. Entrust is one of several security companies which issue certificates and validate that all the information exchanged between your computer and the Bank of America site has been properly encrypted. That means you can safely enter your user name and password for mobile banking access.

Not all web sites actually need encryption. My own site is an example. There's no place on my site where you get asked for sensitive information. There is, however, a sense that EVERY web site should require encrypted connection. That costs money for the site owner. Hosting companies charge extra to apply the encryption. I have not paid for that.

The original visual design of links is still common. Many inline links show as a word or words that are blue with a matching blue underline. Designers have worked hard to get many other colors involved, but the default is still blue text with a blue underline. You certainly have noticed that images can be clicked as links, too. Not all of them say "click me!", of course. Not all web designers like blue underlined links, either.

HEY! that didn't do anything. Did you hover over the button to find out where it was sending you? It is up to you to decide. The button above displays no address because it was not actually a link. However, the button below is an active link. Hovering over this second version of the button shows the location of to which the link goes. In this case, it points to the guide's table of contents. Clicking this next image will send you to the table of contents page. Clicking the "back" button of the browser will return you to here.

You should also note that hovering over the first button shows a normal arrow pointer. However, hovering over the second button displays a hand-shaped pointer. Look for it. In general, a regular link will have a hand pointer in Firefox on Ubuntu. If you use a different browser/operating system, find out what pointer shows for hovering over a link.

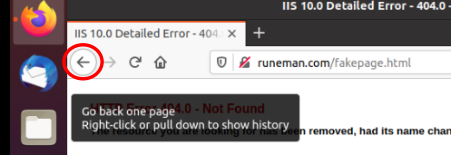

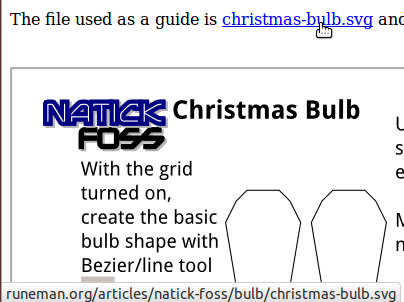

Note the address in the bottom of this image.

The address appears when hovering over a link whether it is underlined blue text or an image.

For a long time, every home page address had the prefix of "www." That was never a requirement, but most domain home pages can be reached that way. As a working example, try these two:

http://www.runeman.org

http://runeman.org

The reason that both forms of internet address work is part of the Internet structure. The specific structure element is called the "Domain Name System" (DNS). The domain name system translates the words humans recognize into a code designed for machine interpretation. Each destination in the system has a number address like 64.71.34.74 in four parts, with periods between the numbers. Such a number address is called the "Internet Protocol" or "IP address." Currently the internet has a bit more than 3.7 billion public addresses. While that seems like it ought to handle our needs, that has turned out to be untrue.

A solution is being implemented. We are converting from IP version 4 to IP version 6. IPv6 handles many more unique address codes.

A billion has 9 zeros.

1000000000 (billion)

The potential number for IPv6 unique addresses has 38 zeros.

100000000000000000000000000000000000000 (does this big number even have a name?)

Remember each zero means multiplying the address space by 10. That's 38 of ten times ten times ten times ten.

As a result, we are now approaching what has been called "The Internet of Things." with the key idea that many, if not all, consumer items will contain a tiny computer which can communicate to servers on the Internet. Each connected item will have an address. Pacemakers will be able to send their measurements of heartbeat to a doctor's office. Your car might report its location and current speed to a computer system which would return information that to adjust speed to make traffic flow more efficient. Google and others have successfully developed a computer controlled automobile which needs no driver to negotiate city streets.

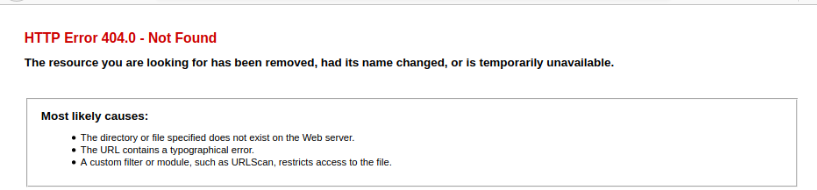

DNS also handles another pain in the neck. http://NatickFOSS.org matches http://natickfoss.org because the DNS system normalizes the capitalization to avoid missed connections. Unfortunately, file names beyond the domain name, on files within a web site, the capital letters DO matter. That means this file has the address http://runeman.org/intro20-04/www.html and is written in lower case letters to match the standard approach. If you make a small change and try to call for the file http://runeman.org/intro20-04/WWW.HTML you will get an error message.

Be careful, especially if you are sending a link to another person. You will be better off copying the link than trying to retype it.

To capture a web address using Firefox:

You can use the mouse to accomplish the same thing (copying a link address), but it isn't quite so quick or easy in my opinion.

As always, get comfortable with a set of steps that you practice over and over. There is no "right" way to use a computer. Do listen to the advice of others. Arguing with them probably won't help either of you. Then do it your way unless you find that you actually like what your friend recommended.

Computer viruses and malware are serious issues of the Internet and World Wide Web. A computer virus is software which makes your computer do things you do not want done. Be alert to the lure "incredible" offers. Clicking links offering too much for too little may be the gateway to a virus or other malware.

The good news is that Ubuntu is a GNU/Linux computer system. Linux was designed from the bottom up to be secure against malware. There is antivirus software available for GNU/Linux and it would be wise to install and use it if you routinely share documents and files with Windows users. While a virus usually targets Windows systems and won't infect your Ubuntu system, you don't want to pass a virus along to your friends who do use Windows.

Another pathway for viruses is called "social engineering" and is often encountered in email messages asking you to be a kind person by sending your details to an unknown person who needs your help.

You also need to be on the lookout for email messages containing offers of money from Nigerian princes, account expiration warnings, etc. These emails often look very official and ask you to click a link to "repair your credit", for example. It might look like the message is from a credit card company or even your own bank. Sometimes, you'll realize you don't actually have THAT credit card and you'll stop yourself from clicking the suggested link. Dick Miller frequently ends our NatickFOSS meetings with good examples or fraudulent SPAM or Phishing emails. Educate yourself. Do Not Panic and think before you click email links.

© 2013- Algot Runeman - Shared using the Creative Commons Attribution license.

Source to cite: - filedate: